During software development, every engineer aims to build products that not only run smoothly today but also remain flexible enough to evolve in the future. However, without proper design orientation from the very first lines of code, a system can easily fall into a trap of growing complexity, becoming difficult to extend and costly to maintain.

That is why developers rely on well-established design principles that have been validated by the software engineering community over time. Among these guiding foundations, SOLID stands out as a core set of principles that helps shape a clear, extensible, and sustainably stable software architecture.

1. What is SOLID?

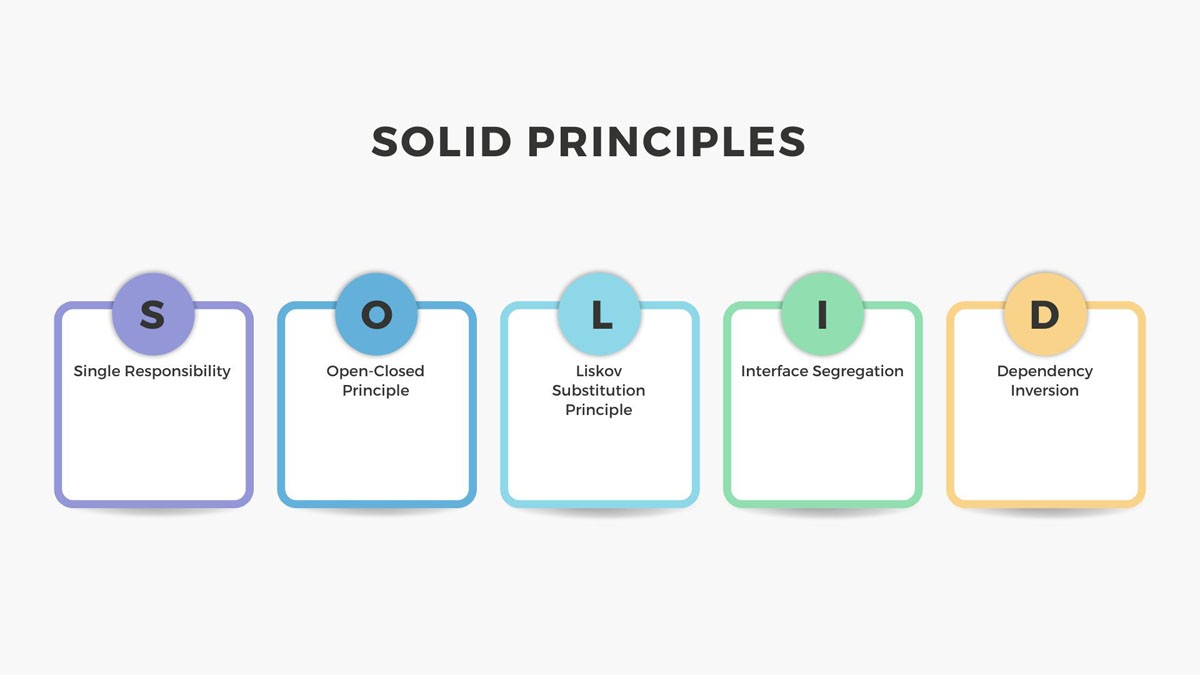

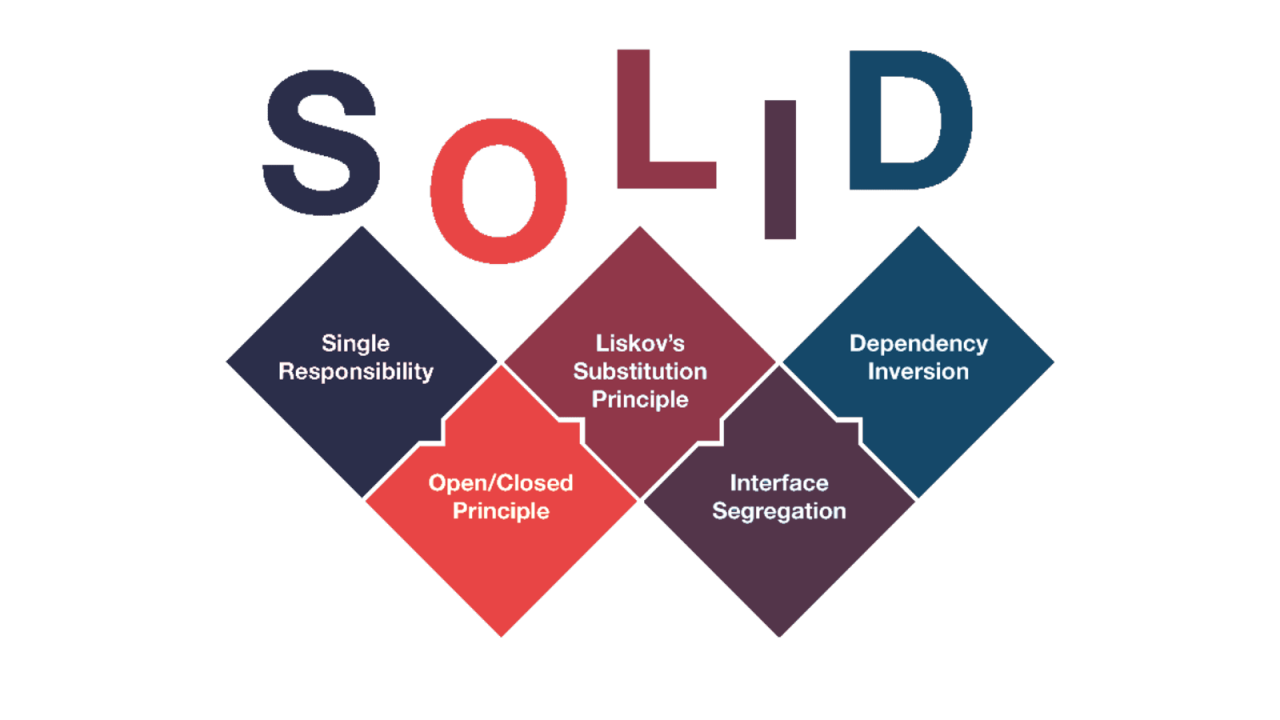

SOLID is an acronym for five software design principles:

- S – Single Responsibility Principle (Principle of Single Responsibility)

- O – Open/Closed Principle (Open/Closed Principle)

- L – Liskov Substitution Principle (Liskov Substitution Principle)

- I – Interface Segregation Principle (Interface Segregation Principle)

- D – Dependency Inversion Principle (Dependency Inversion Principle)

Introduced by Robert C. Martin (Uncle Bob) and popular in the Agile community, this set of principles was created to help software be maintainable, scalable, and testable, while reducing tight coupling between components.

Whether you are programming in Java, C#, Python, or any other OOP language, SOLID remains a crucial foundation for building systems with a clear structure that can “stay healthy” for the long term.

2. How SOLID Principles Work

Before diving into each principle, remember that SOLID is not a set of isolated rules, but a set of mutually supporting principles.

Each principle addresses a specific aspect of software design, but when combined, they form a solid foundation that makes the code both readable and easy to extend and maintain.

Now, let’s explore these five principles one by one – starting with S and ending with D – to see how they work and the practical benefits they bring.

2.1 Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) – Principle of Single Responsibility

A class should have only one reason to change.

Simply put: Each class should handle only one responsibility, and any changes to that class should come from

class Invoice:

def __init__(self, customer: str, amount: float):

self.customer = customer

self.amount = amount

# Responsibility: manage invoice data

def get_amount(self) -> float:

return self.amount

# Additional responsibility: calculate tax

def calculate_tax(self) -> float:

return self.amount * 0.1 # 10% VAT

# Additional responsibility: print invoice details

def print_invoice(self) -> None:

print(f"Customer: {self.customer}")

print(f"Amount: {self.amount}")

print(f"Tax: {self.calculate_tax()}")

# Example usage

invoice = Invoice("Alice", 1000.0)

invoice.print_invoice()

Problem:

- The

Invoiceclass manages data, calculates taxes, and prints invoices all at once. - If we change the way taxes are calculated or invoices are printed, we have to modify the

Invoiceclass directly, which violates SRP.

Applying SRP

// Represents invoice data

public class Invoice {

private String customer;

private double amount;

public Invoice(String customer, double amount) {

this.customer = customer;

this.amount = amount;

}

public String getCustomer() {

return customer;

}

public double getAmount() {

return amount;

}

}

// Handles tax calculation logic

public class TaxCalculator {

public double calculateTax(Invoice invoice) {

return invoice.getAmount() * 0.1; // 10% VAT

}

}

// Responsible for printing invoice details

public class InvoicePrinter {

public void print(Invoice invoice, double tax) {

System.out.println("Customer: " + invoice.getCustomer());

System.out.println("Amount: " + invoice.getAmount());

System.out.println("Tax: " + tax);

}

}

Advantages:

- The

Invoiceclass only manages data. - The

TaxCalculatorclass only handles tax calculation. - The

InvoicePrinterclass only handles printing. - Any changes in logic only need to be made in the specific class, without affecting other parts.

2.2 Open/Closed Principle (OCP) – Open/Closed Principle

A module should be open for extension but closed for modification.

This means: When you need to change functionality, you should extend the class through inheritance or composition, without modifying existing code, to avoid affecting other parts of the system.

Example of OCP Violation:

Suppose we have a payment system that initially only supports credit cards. Later, when we want to add PayPal payment, we modify the existing code directly → violating OCP.

public class PaymentService {

public void processPayment(String type) {

if (type.equals("credit")) {

System.out.println("Processing credit card payment...");

} else if (type.equals("paypal")) {

System.out.println("Processing PayPal payment...");

}

// If a new payment method is added, this code must be modified again

}

}Problem:

- Each time a new payment method is added, you have to open the old file and modify the logic.

- There is a risk of breaking existing functionality.

Applying OCP

We separate the payment methods into an interface and individual implementing classes.

When adding a new method, we only need to create a new class without touching the existing code.

// Interface for payment methods

public interface PaymentMethod {

void pay();

}

// Implementation for credit card payment

public class CreditCardPayment implements PaymentMethod {

@Override

public void pay() {

System.out.println("Processing credit card payment...");

}

}

// Implementation for PayPal payment

public class PayPalPayment implements PaymentMethod {

@Override

public void pay() {

System.out.println("Processing PayPal payment...");

}

}

// Service responsible for processing payments

public class PaymentService {

public void processPayment(PaymentMethod method) {

method.pay();

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

PaymentService service = new PaymentService();

service.processPayment(new CreditCardPayment());

service.processPayment(new PayPalPayment());

// If you want to add a new payment method → simply create a new class that implements PaymentMethod

}

}

Advantages:

- The old code does not need to be modified when adding new features → closed for modification.

- It can be extended by adding new classes → open for extension.

- Reduces the risk of breaking existing functionality.

2.3 Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) – Liskov Substitution Principle

A subclass should be able to replace its parent class without breaking the program’s logic.

In other words, any subclass must fully preserve the behavior of the parent class and must not alter the user’s expectations.

Example of LSP Violation:

Suppose we have a Rectangle class and want to create a Square class that inherits from Rectangle.

It sounds reasonable, but in practice, setting the width/height of Square changes the behavior compared to Rectangle, leading to bugs.

class Rectangle {

protected int width;

protected int height;

public void setWidth(int width) {

this.width = width;

}

public void setHeight(int height) {

this.height = height;

}

public int getArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

class Square extends Rectangle {

@Override

public void setWidth(int width) {

this.width = width;

this.height = width; // Force height to match width

}

@Override

public void setHeight(int height) {

this.height = height;

this.width = height; // Force width to match height

}

}

Proper Application of LSP

Solution: Do not force inheritance if the “is-a” relationship is not truly appropriate.

Here, Square and Rectangle should both implement a common interface like Shape, instead of forcing Square to inherit from Rectangle.

interface Shape {

int getArea();

}

class Rectangle implements Shape {

private int width;

private int height;

public Rectangle(int width, int height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

@Override

public int getArea() {

return width * height;

}

}

class Square implements Shape {

private int side;

public Square(int side) {

this.side = side;

}

@Override

public int getArea() {

return side * side;

}

}public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Shape rect = new Rectangle(5, 10);

Shape square = new Square(5);

System.out.println(rect.getArea()); // 50

System.out.println(square.getArea()); // 25

}

}Advantages:

SquareandRectangleboth adhere to theShapecontract.- The expected behavior of the parent class is not altered.

- The code is easy to understand and free of hidden bugs.

2.4 Interface Segregation Principle (ISP) – Interface Segregation Principle

Classes should not be forced to depend on methods they do not use.

Instead of creating a large interface, break it down into multiple smaller, specialized interfaces. This helps reduce unnecessary dependencies and increases flexibility.

Example of ISP Violation:

Suppose we have a printer management system and define an overly large interface, forcing all printers to implement every method, including those they do not need.

// Oversized interface

interface Machine {

void print();

void scan();

void fax();

}

// Basic printer

class BasicPrinter implements Machine {

@Override

public void print() {

System.out.println("Printing document...");

}

@Override

public void scan() {

// Scan not supported → must leave empty or throw an exception

throw new UnsupportedOperationException("Scan not supported");

}

@Override

public void fax() {

// Fax not supported

throw new UnsupportedOperationException("Fax not supported");

}

}Problem:

BasicPrinterhas to implement bothscan()andfax()even though it does not use them.- This creates unnecessary dependencies and messy code, making maintenance prone to errors.

Applying ISP

Instead of a large interface, split it into multiple specialized interfaces.

interface Printer {

void print();

}

interface Scanner {

void scan();

}

interface Fax {

void fax();

}

// Basic printer that only needs printing capability

class BasicPrinter implements Printer {

@Override

public void print() {

System.out.println("Printing document...");

}

}

// Multi-function printer

class MultiFunctionPrinter implements Printer, Scanner, Fax {

@Override

public void print() {

System.out.println("Printing document...");

}

@Override

public void scan() {

System.out.println("Scanning document...");

}

@Override

public void fax() {

System.out.println("Sending fax...");

}

}Advantages:

- Each class only implements the interfaces it needs.

- Reduces unnecessary dependencies.

- The code is concise and easy to extend.

2.5 Dependency Inversion Principle (DIP) – Dependency Inversion Principle

High-level modules should not depend on low-level modules; both should depend on abstractions.

Meaning: Do not let high-level classes “know too much” about low-level classes. Communicate through interfaces or abstractions, making the system more flexible for changes or testing.

Ví dụ vi phạm DIP:

Suppose we have a notification application.

The NotificationService class (high-level) directly calls EmailSender (low-level).

// Low-level module

class EmailSender {

public void sendEmail(String message) {

System.out.println("Sending Email: " + message);

}

}

// High-level module

class NotificationService {

private EmailSender emailSender = new EmailSender();

public void send(String message) {

emailSender.sendEmail(message);

}

}

Problem:

NotificationServicedirectly depends onEmailSender.- If we want to send via SMS or Push Notification, we have to modify the

NotificationServicecode → violating the principle.

Applying DIP

We create an abstraction (interface) so that both high-level and low-level modules depend on it.

When we want to change the way notifications are sent, we only need to create a new class that implements this interface.

// Abstraction

interface MessageSender {

void sendMessage(String message);

}

// Low-level module: Email

class EmailSender implements MessageSender {

@Override

public void sendMessage(String message) {

System.out.println("Sending Email: " + message);

}

}

// Low-level module: SMS

class SmsSender implements MessageSender {

@Override

public void sendMessage(String message) {

System.out.println("Sending SMS: " + message);

}

}

// High-level module

class NotificationService {

private MessageSender sender;

// Inject dependency via constructor

public NotificationService(MessageSender sender) {

this.sender = sender;

}

public void send(String message) {

sender.sendMessage(message);

}

}

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

NotificationService emailService = new NotificationService(new EmailSender());

emailService.send("Hello via Email!");

NotificationService smsService = new NotificationService(new SmsSender());

smsService.send("Hello via SMS!");

}

}Advantages:

NotificationServicedoes not care about the sending method.- To add a new sending channel, simply create a new class that implements

MessageSender. - Easy to test (you can mock

MessageSenderduring unit testing).

3. Why Apply SOLID?

Applying SOLID is not just because Uncle Bob said so, but because it helps you thrive in the ever-changing world of code:

- Reduced Maintenance Cost

When code is well-organized, adding features or fixing bugs only requires changes in the right place, without “breaking the flow” elsewhere. This is especially important for large projects, where a single wrong line of code can cause the whole team to work overtime. - Increased Reusability

Small, clear, independent modules are like “Lego pieces” – they can be assembled in different places. No need to rewrite from scratch, saving time and effort. - Improved Testability

When components are separated, writing unit tests becomes as easy as “taking an ID photo” – quick, simple, and without interference from unrelated parts. - Better Team Communication

Clear, principle-driven code is immediately understandable → the team doesn’t have to “decode secret messages” when reading each other’s code. This helps onboard new members faster and reduces misunderstandings when collaborating. - Ready for Change

Change requests are inevitable (customers can be unpredictable). SOLID helps the system stay flexible and adaptable, preventing each change from turning into a full-scale “overhaul.”

4. When Should You Apply SOLID — and When Should You Not?

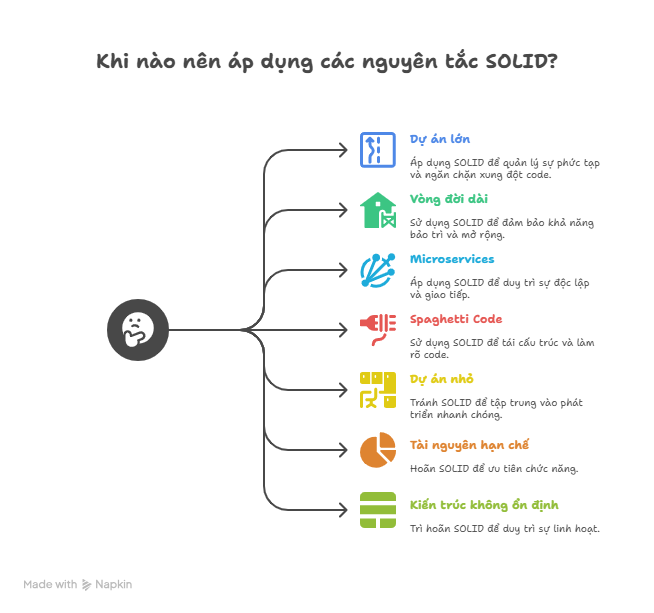

4.1 When to Apply SOLID

- Medium or large projects, especially with large teams

When multiple developers work on the same codebase, there’s a high risk of overlapping code, conflicts, or even “breaking” each other’s work. SOLID acts like traffic rules – everyone stays in their own lane, reducing the chances of collisions along the way. - Systems with a long lifecycle, requiring frequent maintenance and expansion

A long-living system will go through many upgrades and changes. Without applying SOLID, each modification is like removing a block from a Jenga tower – it can easily cause the entire system to collapse. - Microservice architecture or clearly modularized systems

In environments where components need to communicate flexibly yet remain independent, SOLID helps modules “talk” to each other through interfaces, avoiding tight coupling. This is how you keep a microservice from turning into a “micro-mess.” - Projects suffering from spaghetti code

If your code is tangled like a plate of spaghetti, and adding new features feels like a nightmare, then SOLID is the “surgical tool” to untangle, break down, and clean up the architecture.

4.2 When You Don’t Need to Fully Apply SOLID

- Small projects or MVPs (Minimum Viable Products)

At this stage, the goal is to launch the product as quickly as possible to test the idea with users or investors. Over-optimizing the architecture too early can slow down progress and waste effort if the product gets pivoted or dropped. - Limited resources

With a small team, tight deadlines, and a limited budget, the top priority is to get a working product. A clean architecture can be saved for later stages, once the project has proven its value. - Experimental phase with unstable architecture

If you’re still exploring different approaches and the architecture is likely to change entirely, strictly applying SOLID from the start may just lead to wasted time rewriting code. Keep things as simple and flexible as possible.

5. Comparison Between SOLID and Other Principles

I will divide the comparison into 4 main groups:

- SOLID (object-oriented design principles)

- KISS / DRY / YAGNI (general coding principles)

- GRASP (responsibility assignment principles)

- Design Patterns (design templates)

| Principles Group | Main Objective | When to Use | Advantages | Disadvantages / Risks of Overuse | How to Combine with SOLID |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| S (Single Responsibility) – Each class has one reason to change | Reduces complexity, improves maintainability | When a class contains multiple unrelated logic | Code is easy to understand and test | Splitting too small can cause confusion | Combine with DRY to avoid code duplication, and GRASP – High Cohesion to group related functions |

| O (Open/Closed) – Extend without modifying | Allows adding features without breaking existing code | When you need to add functionality without touching existing code | Reduces bugs when extending | Overuse can lead to many complex classes/interfaces | Combine with Design Patterns (Strategy, Decorator) to implement |

| L (Liskov Substitution) – Can be replaced by a subclass | When using inheritance | Ensures consistency | Reduces runtime bugs | Overusing inheritance makes maintenance difficult | Combine with YAGNI to avoid unnecessary inheritance |

| I (Interface Segregation) – Small, focused interfaces | When an interface becomes “fat” | Clients depend only on what they use | Reduces coupling | Too many interfaces cause fragmentation | Combine with KISS to keep interfaces simple |

| D (Dependency Inversion) – Depend on abstractions | When a high-level module depends on a low-level module | Reduces direct dependencies, making testing and mocking easier | Flexible code, easy to replace | Too many abstractions cause complexity | Combine with GRASP – Low Coupling to reduce overall dependencies |

| KISS – Keep It Simple, Stupid | Keep everything as simple as possible | Every stage | Code is easy to understand | Too simple may lack extensibility | Combine with S and I to avoid over-engineering |

| DRY – Don’t Repeat Yourself | Avoid repeating logic | When there is duplicate code | Reduces errors when making changes | Overdoing DRY can force inappropriate code sharing | Combine with S to split classes/modules appropriately |

| YAGNI – You Aren’t Gonna Need It | Don’t code features before they are needed | Feature development phase | Saves time | May need refactoring if really necessary | Combine with O to extend later without modifying existing code |

| GRASP – High Cohesion | Group related functions together | When assigning responsibilities | Code is focused and easy to understand | Overuse → class becomes too large | Supplement for the S principle |

| GRASP – Low Coupling | Reduce the dependencies between modules | When designing a module | Easy to maintain and replace | Requires more design effort | Goes hand in hand with the D in SOLID |

| Design Patterns | Reusable solutions to common problems | When an appropriate pattern is identified | Saves time and ensures clean code | Overuse leads to confusion | Many patterns are created to implement O, D, and L |

When to use which one?

- Starting a Project: KISS, YAGNI, DRY → keep everything simple, avoid doing unnecessary work.

- OOP System Design: Apply SOLID principles to structure classes/modules.

- Responsibility Assignment: Use GRASP alongside SOLID.

- Solving Specific Problems: Choose the appropriate Design Pattern.

Reasonable combination approach

- Start Small with KISS + YAGNI → avoid over-engineering.

- Gradually Develop with SOLID as the system grows larger.

- Use DRY to optimize duplicate code, but ensure the S principle is not violated.

- Use GRASP to help decide who does what in the code.

- Apply Design Patterns when implementing the O or D principles.

6. Conclusion

SOLID is not just a collection of five dry principles. It forms the foundation for building high-quality software that is scalable, maintainable, and less prone to errors. Whether you work with Java, Python, C#, or any other object-oriented language, SOLID remains a reliable guide for writing software in a professional and structured manner.

Learn to apply SOLID step by step. You don’t need to be perfect from the beginning — what matters is understanding the essence of each principle and using them flexibly. As your coding skills grow, adhering to SOLID will eventually become second nature.

7. References

[1] R. C. Martin, Clean Architecture: A Craftsman’s Guide to Software Structure and Design. Prentice Hall, 2017.

[2] R. C. Martin, Agile Software Development: Principles, Patterns, and Practices. Prentice Hall, 2002.

[3] dev.to, “SOLID Principles Explained With Examples.” [Online]. Available: https://dev.to

[4] freeCodeCamp, “SOLID Principles in JavaScript and Other Languages.” [Online]. Available: https://freecodecamp.org

[5] Microsoft, “Official Developer Documentation.” [Online]. Available: https://learn.microsoft.com

[6] JetBrains, “Official Developer Guides and Documentation.” [Online]. Available: https://www.jetbrains.com

[7] ThoughtWorks, “Technology Radar.” [Online]. Available: https://www.thoughtworks.com

[8] OpenDev, “Object-Oriented Programming (OOP): The Core Mindset in Modern Software Development”. Avaliable: https://kienthucmo.com/en/object-oriented-programming-oop-the-core-mindset-in-modern-software-development/