There’s a sad truth that every developer has experienced: just because code runs doesn’t mean it’s good code. Hmm… it’s true. You might write a piece of code that works perfectly today, but return just two weeks later and, not believing your eyes, you’ll ask yourself:

“Hmm… did I really write this mess…!?”

Don’t worry (well, maybe worry a little), welcome to the world of Clean Code — where code not only “runs,” but is also “readable,” “understandable,” and “maintainable without going crazy.”

On the journey to becoming a super-level VIP pro developer, where colleagues no longer fear reading your code, clean code is a secret weapon. It helps you:

- Avoid writing code that your future self will be horrified by.

- Teamwork is no longer a nightmare.

- Easy to debug, easy to extend, and most importantly… easy to live with.

Clean code is not a mystical or overly academic concept. It’s a way to treat yourself and others on your team kindly.

In this article, I will walk you through:

- Decoding what Clean Code is and why it matters.

- Go through the essential principles like DRY, KISS, SOLID (sounds a bit academic but is actually easy to understand, though whether you can apply them in practice is another question).

- Look back at the “legendary” mistakes that everyone has made when writing messy code.

- And finally, review the well-curated materials from coding “veterans,” distilled from the pain and mistakes that you or your colleagues may have caused.

And now… let’s clean up that spaghetti code.

1. What is Clean Code?

The concept of “Clean Code” was introduced and popularized by Robert C. Martin, commonly known by the nickname Uncle Bob – one of the “living legends” in the software development industry. In his book Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship, he defines:

“Clean code always looks like it was written by someone who cares.”

In other words, clean code is code written with respect for the next reader – whether it be a colleague, a client, or yourself after several sleepless weeks due to a deadline.

So, what are the characteristics of clean code?

A piece of code is considered “clean” if it usually:

- Readable: You can understand what the code is doing at a glance without having to guess.

- Understandable: Variables, functions, and classes all have clear and consistent names.

- Easy to modify: When adding new features, you don’t have to “tear down and rebuild” the code.

- Easy to test: Clean code usually separates logic clearly, making it easy to write unit tests.

- Not tangled: Minimal repetition, no messy dependencies, and no “hard-coded” values.

On the other hand, bad code is the kind that makes people exclaim after reading it:

“Hmm…me keep…!!!”

Or they might remain silent, but their facial expressions and eyes… tell a different story.

Why is the definition of clean code important?

Because it is the foundation of every high-quality software project. A system can have thousands of lines of code — if it’s not clean from the start, every fix becomes a “janitor cosplay,” digging through a pile of chaos. This wastes time, breeds new bugs, and makes long-term development difficult.

2. The Importance, Role, and Benefits of Clean Code

Writing clean code isn’t just a good habit — it’s the foundation for building software that can grow sustainably, both technically and humanly. Below are the reasons why clean code should be considered the “top priority” in any serious software project.

2.1. Enhancing Project Sustainability

A software project is never “finished once and for all.” It constantly evolves — adding new features, fixing bugs, optimizing performance, supporting new platforms, and more. That’s why the code must be easy to modify without breaking the entire system.

Clean code helps you refactor with confidence.

For example, if modules are written clearly and without messy dependencies, updating an API or processing logic only requires changes in the right place. Conversely, if the code is tangled, every fix is like “pulling a strand of spaghetti” – easily causing everything to get messed up.

Clean code also helps new team members onboard faster. Instead of spending weeks trying to figure out “what this code does,” a newcomer can grasp the logic just by reading it — thanks to clear naming, an easy-to-follow structure, and well-divided functions by purpose.

2.2. Increasing Productivity and Reliability

Clean code isn’t written faster, but it can be read faster, debugged faster, and makes work more efficient in the long run.

- When functions are concise and variables are clearly named, developers are less likely to make mistakes during debugging or feature expansion.

- When code is easy to test (thanks to clear separation of logic), writing unit tests or setting up CI/CD becomes simpler – reducing the chances of bugs leaking into production.

- When an error occurs, clean code makes it easier to identify the cause, since each part of the system is clearly structured and well-isolated.

A familiar saying in the programming community:

“We read code more often than we write it. So why not write it to be easy to read?”

Clean code saves you hours every week simply because… you spend less time guessing what the code does.

2.3. Strengthening Teamwork Spirit and Idea Communication

Whether you work in a 3-person startup or a 3000-person corporation, software is always a collaborative product. And the source code is the common language among developers.

When someone writes clean code:

- Others can immediately understand the purpose of the code.

- There are fewer misunderstandings when modifying someone else’s code.

- Easier to review pull requests and give feedback.

- Relationships with colleagues improve significantly.

This not only improves communication within the team but also fosters a culture of mutual respect. Clean code is a way to show responsibility — first to yourself, and then to your teammates.

Writing clean code is an act of “helping others understand you” – one of the most important skills in teamwork.

2.4. (Additional) Reducing Long-term Development Costs

This is a benefit that’s rarely mentioned but highly practical: clean code helps reduce the cost of maintenance, bug fixes, and new feature development.

Many companies fall into the trap where, the longer a project runs, the messier the code becomes. Every change risks “breaking the chain,” leading to stagnation. At that point, the cost of merely “keeping the project alive” far exceeds the cost of rewriting it from scratch — all because clean code wasn’t maintained from the very beginning.

3. Core Principles of Clean Code

3.1 Meaningful Naming

Why it’s important:

Variable, function, and class names act as the first layer of documentation for your code. Clear, descriptive names help others (and your future self) quickly understand the purpose and behavior without reading every line. Poorly chosen names force readers to trace logic manually, slow down comprehension, and increase the risk of misusing or misunderstanding the code.

Bad example:

def g(u):

return u.split('@')[1]Good example:

def get_user_email_domain(email):

return email.split('@')[1]You can understand the function’s purpose immediately without having to look into the details.

Avoid: using vague abbreviations (dt, tmp, i2) or generic names (data, process).

3.2 Do One Thing (Each function should do only one thing)

Why it’s important:

Functions that try to handle too many responsibilities become harder to understand, test, and maintain. When logic is tightly coupled inside a large function, even a small change can have unintended side effects elsewhere. Breaking complex logic into smaller, focused functions improves readability, reduces bugs, and makes the codebase easier to extend in the future.

Bad example:

function handleOrder(order) {

validateOrder(order);

saveOrderToDatabase(order);

sendConfirmationEmail(order);

generateInvoice(order);

}Good example:

Break it down:

function validateOrder(order) { ... }

function saveOrder(order) { ... }

function sendEmail(order) { ... }

function generateInvoice(order) { ... }

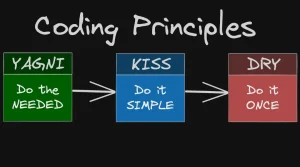

3.3 DRY (Don’t Repeat Yourself)

Why it’s important:

Code repetition means you’ll need to update the same logic in multiple places whenever a change is required. This not only increases the chance of missing one or more spots but also makes debugging and maintenance more time-consuming. Over time, duplicated code leads to inconsistencies and unpredictable behavior across the project.

Bad example:

price_with_tax = price + price * 0.1

# Ở chỗ khác lại viết y chang

total = amount + amount * 0.1Good example:

def add_tax(amount):

TAX_RATE = 0.1

return amount + amount * TAX_RATE3.4 Commenting Correctly

Principle:

- Explain the “why”, not just the “what”.

Comments should describe the reasoning or intent behind the code — why a certain approach was chosen or why an exception is handled in a specific way. This helps future developers understand the context and avoid repeating the same mistakes. - Clear code doesn’t need line-by-line comments.

When code is well-structured and uses meaningful names, it naturally explains itself. Excessive inline comments only add noise and quickly become outdated as the code evolves.

Bad example:

// Add 1 to the **count** variable.

count = count + 1;Good example:

// Add 1 to the count to include the current item.

count += 1;3.5 KISS (Keep It Simple, Stupid)

Why it matters:

The simpler the solution, the easier it is to maintain. Over-engineering (using complex design when it’s not needed) will make you a “victim” of your own creation.

Bad example: Using microservices for a TODO app with 1-2 users.

Good example: Using a simple script or monolith until there is a real need to separate.

3.6 Early Return

Why it matters:

Reduces the depth of if/else, making the code flatter and easier to read.

Bad example:

if (user != null) {

if (user.isActive()) {

sendEmail(user);

}

}Good example:

if (user == null) return;

if (!user.isActive()) return;

sendEmail(user);3.7 SOLID Principles (OOP)

The 5 object-oriented design principles help make systems easier to extend and maintain:

- Single Responsibility – Each class should have only one responsibility.

- Open/Closed – Open for extension, closed for modification.

- Liskov Substitution – A subclass can replace its parent class without breaking the logic.

- Interface Segregation – Small, specialized interfaces.

- Dependency Inversion – Depend on abstractions, not on implementations.

3.8 Writing Automated Tests

Why it matters:

Code without tests is like a “bridge without handrails” – it can still be used, but it’s risky. Tests help to:

- Early bug detection

- Confidence when refactoring

- Ensure the code works as expected

3.9 YAGNI (You Aren’t Gonna Need It)

Meaning:

Don’t write code for features that “might be needed in the future” when there’s no real requirement yet.

Developers often tend to “add just in case” → this leads to increased complexity and harder maintenance.

Learn more: KISS, DRY, YAGNI – 3 Golden Principles in Software Development

3.10 Separation of Concerns

Ý nghĩa:

Mỗi module/class nên giải quyết một “mối quan tâm” (concern) duy nhất. Giao diện UI không nên xử lý logic business, và ngược lại.

Example:

- The Controller layer receives the request →

- Delegates business logic to the Service layer →

- The Repository accesses the data.

This approach helps you modify one part without breaking the entire system.

3.11 Law of Demeter (Principle of Least Knowledge)

Meaning:

An object should only communicate with its “close neighbors” and should not know too much about the internal structure of other objects.

→ Reduces coupling, increases maintainability.

Bad example:

order.customer.address.city.nameThis creates a long dependency chain; changing any layer can cause cascading errors.

3.12 Frequent Refactoring

Meaning:

Clean code doesn’t happen by accident — it’s the result of continuous improvement. After passing tests, take time to refine names, split functions, and eliminate duplication.

Refactoring early helps prevent the buildup of “technical debt.”

3.13 Defensive Programming

Meaning:

Assume inputs can always be incorrect and handle edge cases from the start → avoid unpredictable bugs.

Example:

function divide(a, b) {

if (b === 0) throw new Error("Cannot divide by zero");

return a / b;

}Note: When not to apply extreme measures

- Excessive DRY → creates confusing abstractions, reduces readability.

- Excessive KISS → overly simple solutions, lacking flexibility when requirements change.

- Overly strict YAGNI → sometimes neglects proper architectural preparation, leading to costly refactoring.

- Applying SOLID principles in the wrong context → makes code more complex than the actual benefit.

- …

Learn more: [What is SOLID? Principles, how it works, and practical applications]

4. Official Clean Code Standards/Documentation

| Documents / Standards | Main Content | Practical Value / Application |

|---|---|---|

| Clean Code – Robert C. Martin | A classic book introducing the concept of clean code, naming conventions, organizing functions and classes, error handling, writing comments, and many principles to make code readable and maintainable. | It is a “must-have” book for programmers. It should be read slowly and applied chapter by chapter to real projects. |

| The Clean Coder – Robert C. Martin | It does not focus on coding techniques but discusses the mindset, attitude, responsibility, and professional ethics of software developers. | Helps build a serious mindset, teaches how to say “no” to unreasonable requests, and protects code quality. |

| Refactoring – Martin Fowler | Presents detailed “refactoring patterns” – ways to improve code without changing behavior, along with reasons and strategies. | Extremely useful when cleaning up old code or optimizing architecture. Works well in combination with automated testing. |

| Google Style Guides | Coding style standards for languages such as Python, Java, JavaScript, C++, etc. Includes naming conventions, code formatting, commenting, and file organization. | Helps teams maintain a consistent, readable code style. Can be applied directly or customized for internal projects. |

| SOLID Principles | 5 object-oriented design principles: Single Responsibility, Open/Closed, Liskov Substitution, Interface Segregation, Dependency Inversion. | Improves the scalability and maintainability of OOP systems. Should be learned alongside practical examples to avoid extreme application. |

| DRY / KISS / YAGNI | Three foundational principles: avoid code duplication (DRY), keep solutions simple (KISS), and don’t write what’s not needed (YAGNI). | Helps keep code concise, readable, and reduces maintenance costs. |

5. Common mistakes when writing non-clean code

Although everyone wants their code to be clear and maintainable, in reality, many developers — especially when working under time pressure — often make basic mistakes that lead to messy, hard-to-read, and difficult-to-extend code. These mistakes not only affect individual productivity but also make maintenance and new feature development harder for the entire team. Below are some common mistakes frequently encountered:

- Using vague or meaningless variable/function names: Names like data, temp, or handle() make it unclear what their purpose is. Names should clearly convey the role and meaning of the variable or function.

- Writing overly long or deeply nested functions: A function that does too many things makes maintenance and testing difficult. Break it down into smaller functions, each responsible for a single, clear task.

- Duplicate code, hard to test: Copying the same code in multiple places increases the risk of errors and makes maintenance more time-consuming. Common logic should be extracted into separate functions or modules.

- Improper or excessive comments: Writing notes about obvious things or leaving outdated comments that no longer match the actual code can mislead others. Comments should explain “why”, not “what”.

- Violating the Single Responsibility Principle: A class or function that handles too many tasks becomes difficult to extend and prone to errors. Each component should have only one reason to change.

6. Conclusion

Writing clean code is not a luxury technique for those who have “extra time to polish code beautifully,” but a vital foundation for software to survive, grow, and succeed.

Clean code is like a good book: anyone who opens it can understand the storyline without the author standing by to explain. It helps the whole team confidently develop new features, refactor without fear of “breaking” anything, and keep the project sustainable over time.

A professional programmer not only makes the software work, but also makes others want to work with them — and clean code is the common language that connects them.

Remember: The code you write today is the legacy you leave for the future. Write it as if you will have to maintain it for the next 5 years… because most likely, you will.

7. Reference

[1] R. C. Martin, Clean Code: A Handbook of Agile Software Craftsmanship. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2008.

[2] R. C. Martin, The Clean Coder: A Code of Conduct for Professional Programmers. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall, 2011.

[3] M. Fowler, Refactoring: Improving the Design of Existing Code. Boston, MA: Addison-Wesley, 2018.

[4] OpenDev, “Kienthucmo,” [Online]. Available: https://kienthucmo.com/en/software-engineering/. [Accessed: Oct. 24, 2025].

[6] OpenDev, “What is SOLID? Principles, how it works, and practical applications,” [Online]. Available: https://kienthucmo.com/en/what-is-solid-principles-how-it-works-and-practical-applications/. [Accessed: Oct. 24, 2025].

[7] OpenDev, “KISS, DRY, YAGNI – 3 Golden Principles in Software Development,” [Online]. Available: https://kienthucmo.com/en/kiss-dry-yagni-3-golden-principles-in-software-development/. [Accessed: Oct. 24, 2025].